Word2Vec, Doc2vec & GloVe: Neural Word Embeddings for Natural Language Processing

Contents

- Introduction

- Neural Word Embeddings

- Amusing Word2vec Results

- Just Give Me the Code

- Anatomy of Word2Vec

- Setup, Load and Train

- A Code Example

- Troubleshooting & Tuning Word2Vec

- Word2vec Use Cases

- Foreign Languages

- GloVe (Global Vectors) & Doc2Vec

Introduction to Word2Vec

Word2vec is a two-layer neural net that processes text. Its input is a text corpus and its output is a set of vectors: feature vectors for words in that corpus. While Word2vec is not a deep neural network, it turns text into a numerical form that deep nets can understand. Deeplearning4j implements a distributed form of Word2vec for Java and Scala, which works on Spark with GPUs.

Word2vec’s applications extend beyond parsing sentences in the wild. It can be applied just as well to genes, code, likes, playlists, social media graphs and other verbal or symbolic series in which patterns may be discerned.

Why? Because words are simply discrete states like the other data mentioned above, and we are simply looking for the transitional probabilities between those states: the likelihood that they will co-occur. So gene2vec, like2vec and follower2vec are all possible. With that in mind, the tutorial below will help you understand how to create neural embeddings for any group of discrete and co-occurring states.

The purpose and usefulness of Word2vec is to group the vectors of similar words together in vectorspace. That is, it detects similarities mathematically. Word2vec creates vectors that are distributed numerical representations of word features, features such as the context of individual words. It does so without human intervention.

Given enough data, usage and contexts, Word2vec can make highly accurate guesses about a word’s meaning based on past appearances. Those guesses can be used to establish a word’s association with other words (e.g. “man” is to “boy” what “woman” is to “girl”), or cluster documents and classify them by topic. Those clusters can form the basis of search, sentiment analysis and recommendations in such diverse fields as scientific research, legal discovery, e-commerce and customer relationship management.

The output of the Word2vec neural net is a vocabulary in which each item has a vector attached to it, which can be fed into a deep-learning net or simply queried to detect relationships between words.

Measuring cosine similarity, no similarity is expressed as a 90 degree angle, while total similarity of 1 is a 0 degree angle, complete overlap; i.e. Sweden equals Sweden, while Norway has a cosine distance of 0.760124 from Sweden, the highest of any other country.

Here’s a list of words associated with “Sweden” using Word2vec, in order of proximity:

The nations of Scandinavia and several wealthy, northern European, Germanic countries are among the top nine.

Neural Word Embeddings

The vectors we use to represent words are called neural word embeddings, and representations are strange. One thing describes another, even though those two things are radically different. As Elvis Costello said: “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” Word2vec “vectorizes” about words, and by doing so it makes natural language computer-readable – we can start to perform powerful mathematical operations on words to detect their similarities.

So a neural word embedding represents a word with numbers. It’s a simple, yet unlikely, translation.

Word2vec is similar to an autoencoder, encoding each word in a vector, but rather than training against the input words through reconstruction, as a restricted Boltzmann machine does, word2vec trains words against other words that neighbor them in the input corpus.

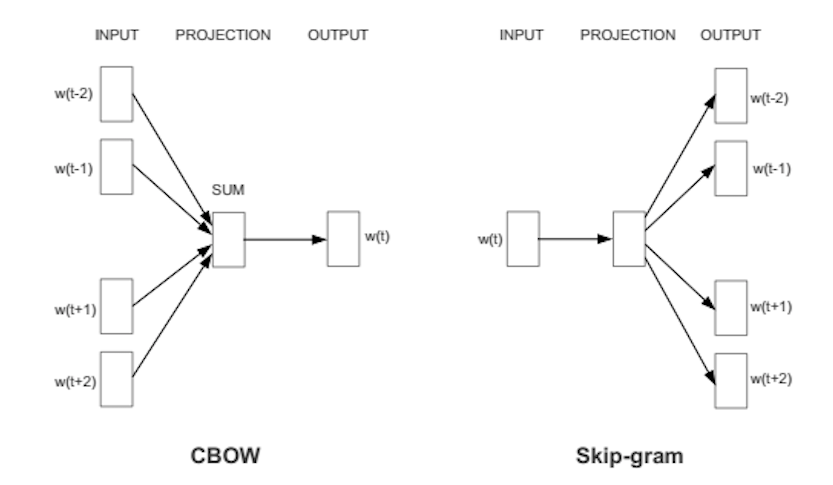

It does so in one of two ways, either using context to predict a target word (a method known as continuous bag of words, or CBOW), or using a word to predict a target context, which is called skip-gram. We use the latter method because it produces more accurate results on large datasets.

When the feature vector assigned to a word cannot be used to accurately predict that word’s context, the components of the vector are adjusted. Each word’s context in the corpus is the teacher sending error signals back to adjust the feature vector. The vectors of words judged similar by their context are nudged closer together by adjusting the numbers in the vector.

Just as Van Gogh’s painting of sunflowers is a two-dimensional mixture of oil on canvas that represents vegetable matter in a three-dimensional space in Paris in the late 1880s, so 500 numbers arranged in a vector can represent a word or group of words.

Those numbers locate each word as a point in 500-dimensional vectorspace. Spaces of more than three dimensions are difficult to visualize. (Geoff Hinton, teaching people to imagine 13-dimensional space, suggests that students first picture 3-dimensional space and then say to themselves: “Thirteen, thirteen, thirteen.” :)

A well trained set of word vectors will place similar words close to each other in that space. The words oak, elm and birch might cluster in one corner, while war, conflict and strife huddle together in another.

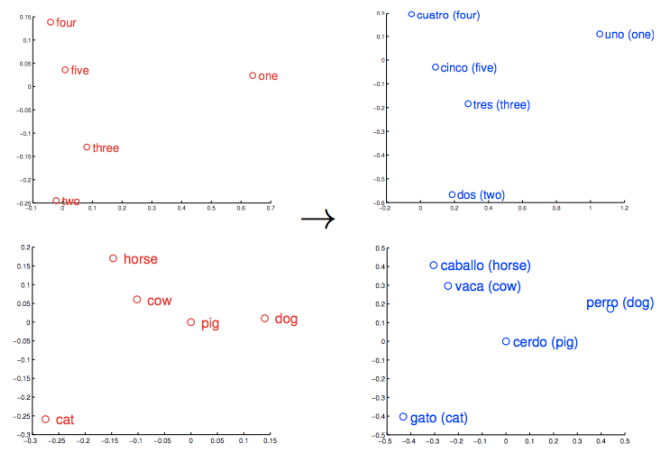

Similar things and ideas are shown to be “close”. Their relative meanings have been translated to measurable distances. Qualities become quantities, and algorithms can do their work. But similarity is just the basis of many associations that Word2vec can learn. For example, it can gauge relations between words of one language, and map them to another.

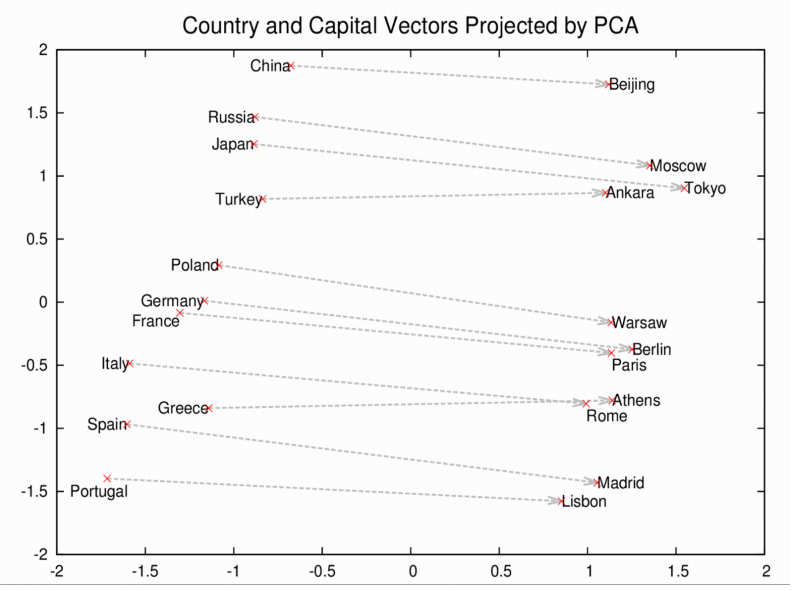

These vectors are the basis of a more comprehensive geometry of words. Not only will Rome, Paris, Berlin and Beijing cluster near each other, but they will each have similar distances in vectorspace to the countries whose capitals they are; i.e. Rome - Italy = Beijing - China. And if you only knew that Rome was the capital of Italy, and were wondering about the capital of China, then the equation Rome -Italy + China would return Beijing. No kidding.

Amusing Word2Vec Results

Let’s look at some other associations Word2vec can produce.

Instead of the pluses, minus and equals signs, we’ll give you the results in the notation of logical analogies, where : means “is to” and :: means “as”; e.g. “Rome is to Italy as Beijing is to China” = Rome:Italy::Beijing:China. In the last spot, rather than supplying the “answer”, we’ll give you the list of words that a Word2vec model proposes, when given the first three elements:

king:queen::man:[woman, Attempted abduction, teenager, girl]

//Weird, but you can kind of see it

China:Taiwan::Russia:[Ukraine, Moscow, Moldova, Armenia]

//Two large countries and their small, estranged neighbors

house:roof::castle:[dome, bell_tower, spire, crenellations, turrets]

knee:leg::elbow:[forearm, arm, ulna_bone]

New York Times:Sulzberger::Fox:[Murdoch, Chernin, Bancroft, Ailes]

//The Sulzberger-Ochs family owns and runs the NYT.

//The Murdoch family owns News Corp., which owns Fox News.

//Peter Chernin was News Corp.'s COO for 13 yrs.

//Roger Ailes is president of Fox News.

//The Bancroft family sold the Wall St. Journal to News Corp.

love:indifference::fear:[apathy, callousness, timidity, helplessness, inaction]

//the poetry of this single array is simply amazing...

Donald Trump:Republican::Barack Obama:[Democratic, GOP, Democrats, McCain]

//It's interesting to note that, just as Obama and McCain were rivals,

//so too, Word2vec thinks Trump has a rivalry with the idea Republican.

monkey:human::dinosaur:[fossil, fossilized, Ice_Age_mammals, fossilization]

//Humans are fossilized monkeys? Humans are what's left

//over from monkeys? Humans are the species that beat monkeys

//just as Ice Age mammals beat dinosaurs? Plausible.

building:architect::software:[programmer, SecurityCenter, WinPcap]

This model was trained on the Google News vocab, which you can import and play with. Contemplate, for a moment, that the Word2vec algorithm has never been taught a single rule of English syntax. It knows nothing about the world, and is unassociated with any rules-based symbolic logic or knowledge graph. And yet it learns more, in a flexible and automated fashion, than most knowledge graphs will learn after a years of human labor. It comes to the Google News documents as a blank slate, and by the end of training, it can compute complex analogies that mean something to humans.

You can also query a Word2vec model for other assocations. Not everything has to be two analogies that mirror each other. (We explain how below….)

- Geopolitics: Iraq - Violence = Jordan

- Distinction: Human - Animal = Ethics

- President - Power = Prime Minister

- Library - Books = Hall

- Analogy: Stock Market ≈ Thermometer

By building a sense of one word’s proximity to other similar words, which do not necessarily contain the same letters, we have moved beyond hard tokens to a smoother and more general sense of meaning.

Just Give Me the Code

Anatomy of Word2vec in DL4J

Here are Deeplearning4j’s natural-language processing components:

- SentenceIterator/DocumentIterator: Used to iterate over a dataset. A SentenceIterator returns strings and a DocumentIterator works with inputstreams.

- Tokenizer/TokenizerFactory: Used in tokenizing the text. In NLP terms, a sentence is represented as a series of tokens. A TokenizerFactory creates an instance of a tokenizer for a “sentence.”

- VocabCache: Used for tracking metadata including word counts, document occurrences, the set of tokens (not vocab in this case, but rather tokens that have occurred), vocab (the features included in both bag of words as well as the word vector lookup table)

- Inverted Index: Stores metadata about where words occurred. Can be used for understanding the dataset. A Lucene index with the Lucene implementation[1] is automatically created.

While Word2vec refers to a family of related algorithms, this implementation uses Skip-Gram Negative Sampling.

Word2Vec Setup

Create a new project in IntelliJ using Maven. If you don’t know how to do that, see our Quickstart page. Then specify these properties and dependencies in the POM.xml file in your project’s root directory (You can check Maven for the most recent versions – please use those…).

Loading Data

Now create and name a new class in Java. After that, you’ll take the raw sentences in your .txt file, traverse them with your iterator, and subject them to some sort of preprocessing, such as converting all words to lowercase.

String filePath = new ClassPathResource("raw_sentences.txt").getFile().getAbsolutePath();

log.info("Load & Vectorize Sentences....");

// Strip white space before and after for each line

SentenceIterator iter = new BasicLineIterator(filePath);

If you want to load a text file besides the sentences provided in our example, you’d do this:

log.info("Load data....");

SentenceIterator iter = new LineSentenceIterator(new File("/Users/cvn/Desktop/file.txt"));

iter.setPreProcessor(new SentencePreProcessor() {

@Override

public String preProcess(String sentence) {

return sentence.toLowerCase();

}

});

That is, get rid of the ClassPathResource and feed the absolute path of your .txt file into the LineSentenceIterator.

SentenceIterator iter = new LineSentenceIterator(new File("/your/absolute/file/path/here.txt"));

In bash, you can find the absolute file path of any directory by typing pwd in your command line from within that same directory. To that path, you’ll add the file name and voila.

Tokenizing the Data

Word2vec needs to be fed words rather than whole sentences, so the next step is to tokenize the data. To tokenize a text is to break it up into its atomic units, creating a new token each time you hit a white space, for example.

// Split on white spaces in the line to get words

TokenizerFactory t = new DefaultTokenizerFactory();

t.setTokenPreProcessor(new CommonPreprocessor());

That should give you one word per line.

Training the Model

Now that the data is ready, you can configure the Word2vec neural net and feed in the tokens.

log.info("Building model....");

Word2Vec vec = new Word2Vec.Builder()

.minWordFrequency(5)

.iterations(1)

.layerSize(100)

.seed(42)

.windowSize(5)

.iterate(iter)

.tokenizerFactory(t)

.build();

log.info("Fitting Word2Vec model....");

vec.fit();

This configuration accepts a number of hyperparameters. A few require some explanation:

- batchSize is the amount of words you process at a time.

- minWordFrequency is the minimum number of times a word must appear in the corpus. Here, if it appears less than 5 times, it is not learned. Words must appear in multiple contexts to learn useful features about them. In very large corpora, it’s reasonable to raise the minimum.

- useAdaGrad - Adagrad creates a different gradient for each feature. Here we are not concerned with that.

- layerSize specifies the number of features in the word vector. This is equal to the number of dimensions in the featurespace. Words represented by 500 features become points in a 500-dimensional space.

- iterations this is the number of times you allow the net to update its coefficients for one batch of the data. Too few iterations mean it may not have time to learn all it can; too many will make the net’s training longer.

- learningRate is the step size for each update of the coefficients, as words are repositioned in the feature space.

- minLearningRate is the floor on the learning rate. Learning rate decays as the number of words you train on decreases. If learning rate shrinks too much, the net’s learning is no longer efficient. This keeps the coefficients moving.

- iterate tells the net what batch of the dataset it’s training on.

- tokenizer feeds it the words from the current batch.

- vec.fit() tells the configured net to begin training.

An example for uptraining your previously trained word vectors is here.

Evaluating the Model, Using Word2vec

The next step is to evaluate the quality of your feature vectors.

// Write word vectors

WordVectorSerializer.writeWordVectors(vec, "pathToWriteto.txt");

log.info("Closest Words:");

Collection<String> lst = vec.wordsNearest("day", 10);

System.out.println(lst);

UiServer server = UiServer.getInstance();

System.out.println("Started on port " + server.getPort());

//output: [night, week, year, game, season, during, office, until, -]

The line vec.similarity("word1","word2") will return the cosine similarity of the two words you enter. The closer it is to 1, the more similar the net perceives those words to be (see the Sweden-Norway example above). For example:

double cosSim = vec.similarity("day", "night");

System.out.println(cosSim);

//output: 0.7704452276229858

With vec.wordsNearest("word1", numWordsNearest), the words printed to the screen allow you to eyeball whether the net has clustered semantically similar words. You can set the number of nearest words you want with the second parameter of wordsNearest. For example:

Collection<String> lst3 = vec.wordsNearest("man", 10);

System.out.println(lst3);

//output: [director, company, program, former, university, family, group, such, general]

Visualizing the Model

We rely on TSNE to reduce the dimensionality of word feature vectors and project words into a two or three-dimensional space. The full DL4J/ND4J example for TSNE is here.

Nd4j.setDataType(DataBuffer.Type.DOUBLE);

List<String> cacheList = new ArrayList<>(); //cacheList is a dynamic array of strings used to hold all words

//STEP 2: Turn text input into a list of words

log.info("Load & Vectorize data....");

File wordFile = new ClassPathResource("words.txt").getFile(); //Open the file

//Get the data of all unique word vectors

Pair<InMemoryLookupTable,VocabCache> vectors = WordVectorSerializer.loadTxt(wordFile);

VocabCache cache = vectors.getSecond();

INDArray weights = vectors.getFirst().getSyn0(); //seperate weights of unique words into their own list

for(int i = 0; i < cache.numWords(); i++) //seperate strings of words into their own list

cacheList.add(cache.wordAtIndex(i));

//STEP 3: build a dual-tree tsne to use later

log.info("Build model....");

BarnesHutTsne tsne = new BarnesHutTsne.Builder()

.setMaxIter(iterations).theta(0.5)

.normalize(false)

.learningRate(500)

.useAdaGrad(false)

// .usePca(false)

.build();

//STEP 4: establish the tsne values and save them to a file

log.info("Store TSNE Coordinates for Plotting....");

String outputFile = "target/archive-tmp/tsne-standard-coords.csv";

(new File(outputFile)).getParentFile().mkdirs();

tsne.fit(weights);

tsne.saveAsFile(cacheList, outputFile);

Saving, Reloading & Using the Model

You’ll want to save the model. The normal way to save models in Deeplearning4j is via the serialization utils (Java serialization is akin to Python pickling, converting an object into a series of bytes).

log.info("Save vectors....");

WordVectorSerializer.writeWord2VecModel(vec, "pathToSaveModel.txt");

This will save the vectors to a file called pathToSaveModel.txt that will appear in the root of the directory where Word2vec is trained. The output in the file should have one word per line, followed by a series of numbers that together are its vector representation.

To keep working with the vectors, simply call methods on vec like this:

Collection<String> kingList = vec.wordsNearest(Arrays.asList("king", "woman"), Arrays.asList("queen"), 10);

The classic example of Word2vec’s arithmetic of words is “king - queen = man - woman” and its logical extension “king - queen + woman = man”.

The example above will output the 10 nearest words to the vector king - queen + woman, which should include man. The first parameter for wordsNearest has to include the “positive” words king and woman, which have a + sign associated with them; the second parameter includes the “negative” word queen, which is associated with the minus sign (positive and negative here have no emotional connotation); the third is the length of the list of nearest words you would like to see. Remember to add this to the top of the file: import java.util.Arrays;.

Any number of combinations is possible, but they will only return sensible results if the words you query occurred with enough frequency in the corpus. Obviously, the ability to return similar words (or documents) is at the foundation of both search and recommendation engines.

You can reload the vectors into memory like this:

Word2Vec word2Vec = WordVectorSerializer.readWord2VecModel("pathToSaveModel.txt");

You can then use Word2vec as a lookup table:

WeightLookupTable weightLookupTable = word2Vec.lookupTable();

Iterator<INDArray> vectors = weightLookupTable.vectors();

INDArray wordVectorMatrix = word2Vec.getWordVectorMatrix("myword");

double[] wordVector = word2Vec.getWordVector("myword");

If the word isn’t in the vocabulary, Word2vec returns zeros.

Importing Word2vec Models

The Google News Corpus model we use to test the accuracy of our trained nets is hosted on S3. Users whose current hardware takes a long time to train on large corpora can simply download it to explore a Word2vec model without the prelude.

If you trained with the C vectors or Gensimm, this line will import the model.

File gModel = new File("/Developer/Vector Models/GoogleNews-vectors-negative300.bin.gz");

Word2Vec vec = WordVectorSerializer.readWord2VecModel(gModel);

Remember to add import java.io.File; to your imported packages.

With large models, you may run into trouble with your heap space. The Google model may take as much as 10G of RAM, and the JVM only launches with 256 MB of RAM, so you have to adjust your heap space. You can do that either with a bash_profile file (see our Troubleshooting section), or through IntelliJ itself:

//Click:

IntelliJ Preferences > Compiler > Command Line Options

//Then paste:

-Xms1024m

-Xmx10g

-XX:MaxPermSize=2g

N-grams & Skip-grams

Words are read into the vector one at a time, and scanned back and forth within a certain range. Those ranges are n-grams, and an n-gram is a contiguous sequence of n items from a given linguistic sequence; it is the nth version of unigram, bigram, trigram, four-gram or five-gram. A skip-gram simply drops items from the n-gram.

The skip-gram representation popularized by Mikolov and used in the DL4J implementation has proven to be more accurate than other models, such as continuous bag of words, due to the more generalizable contexts generated.

This n-gram is then fed into a neural network to learn the significance of a given word vector; i.e. significance is defined as its usefulness as an indicator of certain larger meanings, or labels.

A Working Example

Please note : The code below may be outdated. For updated examples, please see our dl4j-examples repository on Github.

Now that you have a basic idea of how to set up Word2Vec, here’s one example of how it can be used with DL4J’s API:

After following the instructions in the Quickstart, you can open this example in IntelliJ and hit run to see it work. If you query the Word2vec model with a word isn’t contained in the training corpus, it will return null.

Troubleshooting & Tuning Word2Vec

Q: I get a lot of stack traces like this

java.lang.StackOverflowError: null

at java.lang.ref.Reference.<init>(Reference.java:254) ~[na:1.8.0_11]

at java.lang.ref.WeakReference.<init>(WeakReference.java:69) ~[na:1.8.0_11]

at java.io.ObjectStreamClass$WeakClassKey.<init>(ObjectStreamClass.java:2306) [na:1.8.0_11]

at java.io.ObjectStreamClass.lookup(ObjectStreamClass.java:322) ~[na:1.8.0_11]

at java.io.ObjectOutputStream.writeObject0(ObjectOutputStream.java:1134) ~[na:1.8.0_11]

at java.io.ObjectOutputStream.defaultWriteFields(ObjectOutputStream.java:1548) ~[na:1.8.0_11]

A: Look inside the directory where you started your Word2vec application. This can, for example, be an IntelliJ project home directory or the directory where you typed Java at the command line. It should have some directories that look like:

ehcache_auto_created2810726831714447871diskstore

ehcache_auto_created4727787669919058795diskstore

ehcache_auto_created3883187579728988119diskstore

ehcache_auto_created9101229611634051478diskstore

You can shut down your Word2vec application and try to delete them.

Q: Not all of the words from my raw text data are appearing in my Word2vec object…

A: Try to raise the layer size via .layerSize() on your Word2Vec object like so

Word2Vec vec = new Word2Vec.Builder().layerSize(300).windowSize(5)

.layerSize(300).iterate(iter).tokenizerFactory(t).build();

Q: How do I load my data? Why does training take forever?

A: If all of your sentences have been loaded as one sentence, Word2vec training could take a very long time. That’s because Word2vec is a sentence-level algorithm, so sentence boundaries are very important, because co-occurrence statistics are gathered sentence by sentence. (For GloVe, sentence boundaries don’t matter, because it’s looking at corpus-wide co-occurrence. For many corpora, average sentence length is six words. That means that with a window size of 5 you have, say, 30 (random number here) rounds of skip-gram calculations. If you forget to specify your sentence boundaries, you may load a “sentence” that’s 10,000 words long. In that case, Word2vec would attempt a full skip-gram cycle for the whole 10,000-word “sentence”. In DL4J’s implementation, a line is assumed to be a sentence. You need plug in your own SentenceIterator and Tokenizer. By asking you to specify how your sentences end, DL4J remains language-agnostic. UimaSentenceIterator is one way to do that. It uses OpenNLP for sentence boundary detection.

Q: Why is there such a difference in performance when feeding whole documents as one “sentence” vs splitting into Sentences?

A:If average sentence contains 6 words, and window size is 5, maximum theoretical number of 10 skipgram rounds will be achieved on 0 words. Sentence isn’t long enough to have full window set with words. Rough maximum number of 5 sg rounds is available there for all words in such sentence.

But if your “sentence” is 1000k words length, you’ll have 10 skipgram rounds for every word in this sentence, excluding the first 5 and last five. So, you’ll have to spend WAY more time building model + cooccurrence statistics will be shifted due to the absense of sentence boundaries.

Q: How does Word2Vec Use Memory?

A: The major memory consumer in w2v is weghts matrix. Math is simple there: NumberOfWords x NumberOfDimensions x 2 x DataType memory footprint.

So, if you build w2v model for 100k words using floats, and 100 dimensions, your memory footprint will be 100k x 100 x 2 x 4 (float size) = 80MB RAM just for matri + some space for strings, variables, threads etc.

If you load pre-built model, it uses roughly 2 times less RAM then during build time, so it’s 40MB RAM.

And the most popular model used so far is Google News model. There’s 3M words, and vector size 300. That gives us 3.6GB only to load model. And you have to add 3M of strings, that do not have constant size in java. So, usually that’s something around 4-6GB for loaded model depending on jvm version/supplier, gc state and phase of the moon.

Q: I did everything you said and the results still don’t look right.

A: Make sure you’re not hitting into normalization issues. Some tasks, like wordsNearest(), use normalized weights by default, and others require non-normalized weights. Pay attention to this difference.

Use Cases

Google Scholar keeps a running tally of the papers citing Deeplearning4j’s implementation of Word2vec here.

Kenny Helsens, a data scientist based in Belgium, applied Deeplearning4j’s implementation of Word2vec to the NCBI’s Online Mendelian Inheritance In Man (OMIM) database. He then looked for the words most similar to alk, a known oncogene of non-small cell lung carcinoma, and Word2vec returned: “nonsmall, carcinomas, carcinoma, mapdkd.” From there, he established analogies between other cancer phenotypes and their genotypes. This is just one example of the associations Word2vec can learn on a large corpus. The potential for discovering new aspects of important diseases has only just begun, and outside of medicine, the opportunities are equally diverse.

Andreas Klintberg trained Deeplearning4j’s implementation of Word2vec on Swedish, and wrote a thorough walkthrough on Medium.

Word2Vec is especially useful in preparing text-based data for information retrieval and QA systems, which DL4J implements with deep autoencoders.

Marketers might seek to establish relationships among products to build a recommendation engine. Investigators might analyze a social graph to surface members of a single group, or other relations they might have to location or financial sponsorship.

Google’s Word2vec Patent

Word2vec is a method of computing vector representations of words introduced by a team of researchers at Google led by Tomas Mikolov. Google hosts an open-source version of Word2vec released under an Apache 2.0 license. In 2014, Mikolov left Google for Facebook, and in May 2015, Google was granted a patent for the method, which does not abrogate the Apache license under which it has been released.

Foreign Languages

While words in all languages may be converted into vectors with Word2vec, and those vectors learned with Deeplearning4j, NLP preprocessing can be very language specific, and requires tools beyond our libraries. The Stanford Natural Language Processing Group has a number of Java-based tools for tokenization, part-of-speech tagging and named-entity recognition for languages such as Mandarin Chinese, Arabic, French, German and Spanish. For Japanese, NLP tools like Kuromoji are useful. Other foreign-language resources, including text corpora, are available here.

GloVe: Global Vectors

Loading and saving GloVe models to word2vec can be done like so:

WordVectors wordVectors = WordVectorSerializer.loadTxtVectors(new File("glove.6B.50d.txt"));

Sequence Vectors

Deeplearning4j has a class called SequenceVectors, which is one level of abstraction above word vectors, and which allows you to extract features from any sequence, including social media profiles, transactions, proteins, etc. If data can be described as sequence, it can be learned via skip-gram and hierarchic softmax with the AbstractVectors class. This is compatible with the DeepWalk algorithm, also implemented in Deeplearning4j.

Word2Vec Features on Deeplearning4j

- Weights update after model serialization/deserialization was added. That is, you can update model state with, say, 200GB of new text by calling

loadFullModel, addingTokenizerFactoryandSentenceIteratorto it, and callingfit()on the restored model. - Option for multiple datasources for vocab construction was added.

- Epochs and Iterations can be specified separately, although they are both typically “1”.

- Word2Vec.Builder has this option:

hugeModelExpected. If set totrue, the vocab will be periodically truncated during the build. - While

minWordFrequencyis useful for ignoring rare words in the corpus, any number of words can be excluded to customize. - Two new WordVectorsSerialiaztion methods have been introduced:

writeFullModelandloadFullModel. These save and load a full model state. - A decent workstation should be able to handle a vocab with a few million words. Deeplearning4j’s Word2vec imlementation can model a few terabytes of data on a single machine. Roughly, the math is:

vectorSize * 4 * 3 * vocab.size().

Doc2vec & Other NLP Resources

- DL4J Example of Text Classification With Word2vec & RNNs

- DL4J Example of Text Classification With Paragraph Vectors

- Doc2vec, or Paragraph Vectors, With Deeplearning4j

- Thought Vectors, Natural Language Processing & the Future of AI

- Quora: How Does Word2vec Work?

- Quora: What Are Some Interesting Word2Vec Results?

- Word2Vec: an introduction; Folgert Karsdorp

- Mikolov’s Original Word2vec Code @Google

- word2vec Explained: Deriving Mikolov et al.’s Negative-Sampling Word-Embedding Method; Yoav Goldberg and Omer Levy

- Bag of Words & Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF)

- Advances in Pre-Training Distributed Word Representations - by Mikolov et al

Other Machine Learning Tutorials

- Multilayer Perceptron (MLPs) for Classification

- Eigenvectors, Eigenvalues, Covariance, PCA and Entropy

- LSTMs and Recurrent Networks

- Introduction to Deep Neural Networks

- Deep Convolutional Networks

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

- Deep Reinforcement Learning

- Quickstart Examples for Deeplearning4j

- ND4J: A Tensor Library for the JVM

- MNIST for Beginners

- Glossary of Deep-Learning and Neural-Net Terms

- Restricted Boltzmann Machines

- Inference: Machine Learning Model Server

- AI vs. Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning

- Convolutional Networks (CNNs)

- Multilayer Perceptron (MLPs) for Classification

- Graph Data and Deep Learning

- Symbolic Reasoning (Symbolic AI) & Deep Learning

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo & Machine Learning

- Neural Networks & Regression

- Introduction to Decision Trees

- Introduction to Random Forests

- Open Datasets for Machine Learning

Word2Vec in Literature

It's like numbers are language, like all the letters in the language are turned into numbers, and so it's something that everyone understands the same way. You lose the sounds of the letters and whether they click or pop or touch the palate, or go ooh or aah, and anything that can be misread or con you with its music or the pictures it puts in your mind, all of that is gone, along with the accent, and you have a new understanding entirely, a language of numbers, and everything becomes as clear to everyone as the writing on the wall. So as I say there comes a certain time for the reading of the numbers.

-- E.L. Doctorow, Billy Bathgate